Bosnia-Herzegovina: The war visible in a museum, 30 years on

The Bosnia-Herzegovina War lasted from March 1992 to December 1995. Three decades later, the after-effects are still visible, and the conflict in Ukraine reawakens old demons.

The Bosnia-Herzegovina War lasted from March 1992 to December 1995. Three decades later, the after-effects are still visible, and the conflict in Ukraine reawakens old demons.

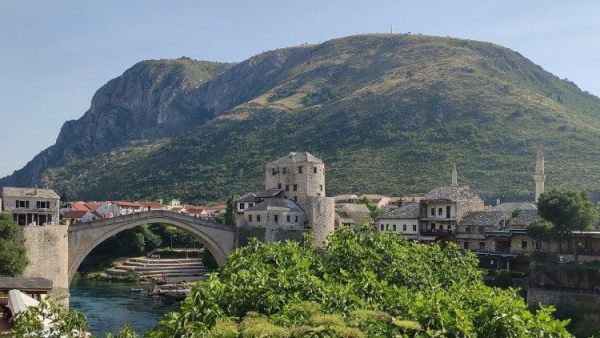

The old town of Mostar in Bosnia Herzegovina offers its visitors the possibility to visit a "War and Genocide Museum". Created from scratch four years ago by a small number of volunteers anxious to keep alive the memory of the war that tore the former Yugoslav republic apart between 1992 and 1995, the museum is made up of numerous personal stories.

At the time of its creation, the exhibition was housed in a single room. Then the inhabitants of Mostar began to bring more objects and their experiences. The museum had to move and expand in order to display everything.

The story of Dr. Eniz Begic

The clothes and shoes amid the human remains found in the countless mass graves scattered throughout Bosnia reveal the experience of the people of Mostar.

We learn of the story of Dr. Eniz Begic, a Bosnian Muslim doctor, who before the war, treated all his patients without asking if they were Croats, Serbs or Bosnians. He was arrested by the Bosnian Serbs, under the leadership of General Ratko Mladic, and he was taken to the Omarska concentration camp.

One of the doctor’s patients shared his testimony with the museum. The patient recounts that he went in search of the doctor until, through the help of a friendly Bosnian-Serb soldier, he was able to send food to the doctor everyday because he had sworn that the doctor would not lack anything throughout his detention.

At the end of the war, the doctor was never found but testimonies from the detention camp revealed that Dr. Begic regularly distributed the food that came to him to the other prisoners "without keeping anything for himself". The circumstances around his death are still unclear.

The museum is full of testimonies such as this one. It also contains many photos taken by prisoners or soldiers that were not shown in the press at that time. Videos are also projected to visitors. They offer the account of direct witnesses of the worst moments of Mostar, of UN peacekeepers, who in highlight the insufficiency of their manpower to protect the civilians at the arrival of the Bosnian Serb troops. Many summary executions are also documented.

A shadow of the war in Ukraine

When entering this small museum, it is impossible not to make a similar connection with the war raging today between Russia and Ukraine. The parallel can be made by looking at each photo, by reading the testimonies.

In the rear of the museum in Mostar, there is a room covered with messages from visitors in different languages. The most recent writings speak of the war in Ukraine.

The contrast with the bustling and noisy activity of the old city is obvious. The war is 30 years old, the pandemic is over, and the tourists are coming back as numerous as before. Bells are ringing, a muezzin is calling for prayer and communities are living together again.

Of the more than 100,000 habitants of Mostar, 48 percent are Croats, 44 percent Bosnians and 4 percent Serbs. The Serbs are the only community that did not return to the city after the war. In fact they were 18 percent of the population before 1992.

However, the current composition of the community has a different pattern. If, before the war, Serbs, Croats and Bosnians lived in the same neighborhoods, today the areas are "ethnically" divided. The Croats are mostly on the west bank of the Neretva, the river that runs through Mostar, while the Bosnians live on the east bank. People pass and work on either side of the bridge without any problems, but the feeling that each community has its own territory remains.

Another consequence of the war is that there are fewer intermarriages. A blacksmith in the old town explains that he is Muslim but his wife is Catholic. Between two strikes of his hammer on a copper decoration he was working on, the 60-year-old described how he fought with the Bosnian forces when his wife's cousins were on the other side in the Bosnian Croat armed forces. "All that is in the past," he says, "we all get together as a family for both Muslim and Christian holidays," he continues, blaming the current tensions on "politicians" whom he describes as "corrupt."

The old Ottoman bridge of Mostar always attracts the curious. It is the symbol of the city, but seems to have lost its main function which was to unite the communities. It was destroyed on November 9, 1993 by a Croatian bombing, to further isolate the besieged Bosnian population. Although rebuilt identically and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005, it reveals the pain and hatred that fractured the historical multi-ethnicity of the place.

The war has not disappeared completely. It has left traces all over the city. Even if reconstruction is well underway, gutted buildings and the impacts on the walls remind everyone of the tragedy experienced, the bombings, the sniper fire, the lives lost in a bid to fill a jerry can of water. The cemeteries of Mostar show the extent of the waste of human life. In several rows, the graves display the age of the dead. Most of them are under thirty. The youngest is 19. On a street corner, a painting on a stone says to whoever looks at it: "don't forget".

Milan, aged 17, who has a summer job in a Turkish cultural center in Mostar, only knows about the war from what he has learnt in school and what his family told him. "We are still living with the consequences," he says, before launching into a socio-economic explanation: "There is no work for everyone and people are leaving the country. I can't say that we are poor, but it was better before." Before, says Milan, it was the Yugoslavian period of Marshal Tito. "We were a country that developed after the Second World War. We had growth and a powerful army," he adds.

Fragile peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The war in Ukraine has threatened to awaken old demons. Shortly after the outbreak of hostilities between Kiev and Moscow on February 24, Bosnia and Herzegovina's collegial presidency threatened to fall apart.

The collegial presidency has been under constant tension after being plunged into a political crisis following the 2018 elections marked by the victory of Serb and Bosniak nationalists that did not allow the formation of a central government of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. More so, the position taken by Milorad Dodik, the Serbian representative of the Presidency, in favour of Moscow has further weakened an already unstable situation. For the time being, Dodik has backed down and reassured the European Union of the need for Bosnia-Herzegovina to remain "neutral" in this conflict. This move also reassures Menvirsa, 32-year-old Bosnian Muslim and curator of the Museum of War and Genocide in Mostar, who only aspires to live in peace.

This is not Milorad Dodik's first attempt. On January 9, he had 800 Republika Srpska soldiers march in Banja Luka on a Serb nationalist holiday which was declared illegal by the Bosnian Constitutional Court because it discriminated against the Bosnian Muslim and Croatian Catholic communities. Thirty years ago, on January 9, 1992, the Bosnian Serbs declared the creation of their own state in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Two months later, a war broke out that left more than a hundred thousand dead.

The horror and brutality of that war, documented by images and the accounts of survivors, have emerged from the past and seem to be visible today in Ukraine. This is demonstrated by two images taken thirty years apart, and revealing the "existential cainism" denounced by Pope Francis in April. The first is a photo from the Mostar museum. It shows a woman in her eighth month of pregnancy shot in the stomach with her unborn child. The other picture is from March 9. It is that of the evacuation of a pregnant woman, fatally wounded in the bombing of a maternity hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine.

With its history, the Mostar bridge fully illustrates the repeated appeals of Pope Francis, reiterated in his greetings to the diplomatic corps last January. Not without difficulties, the old bridge strives to reunite families and communities torn apart, to promote forgiveness and reconciliation. Its vocation would be to become once again a "bridge of encounter between peoples, [...] of brotherhood and peace" in opposition to the "deafening noise of wars and conflicts."

Jean-Charles Putzolu

Source: vaticannews.va